Long ago I had popular thread on a social media site about the dynamical systems perspective of the reproduction number $R_0$ (R-naught). Here, I walk through it similarly to my treatment from before. The main pre-requisite is a solid understanding of calculus - in particular, knowing that a negative derivative means a function is decreasing and a positive derivative means it's decreasing. It helps a lot if you've seen differential equations in the past and are comfortable with equations with multiple variables as well, but it's not at all required to know how to find analytic solutions to differential equations.

So first, a preliminary: $R_0$ is a general term describing the reproductive capacity of an organism. In epidemiology it refers to the number of secondary cases that result from a single case in an entirely susceptible population. One might also encounter it in an ecological context as well, referring to the average number of offspring for an organism. The base idea, that reproduction above replacement rate is typically required for population growth, is the same in both contexts. It's a pretty common theme that ideas in math-epi have analogues in population dynamics, with diseases playing roles as predators and hosts analogous to prey.

To give a little taste of how the mathematical side of some of these models looks, I'm going to introduce you to one of the most humble and familiar models a mathematical epidemiologist will encounter: the SIR model. It's named as such because it's a system of three differential equations, one for each "compartment" of people: Susceptible, Infectious (or Infected), and Recovered classes.

We'll be using $S(t)$, $I(t)$, and $R(t)$ to denote the populations in each class at a given time $t$. For simplicity in notation, we often just use the letters $S$, $I$, and $R$ without the $(t)$ designation. Here's the system (isn't it cute?):

$$\begin{aligned} \frac{dS}{dt} &= \Lambda - \beta SI - \mu S \\ \frac{dI}{dt} &= \beta SI - \alpha I - \mu I \\ \frac{dR}{dt} &= \alpha I - \mu R \end{aligned}$$

If you're familiar with calculus notation, you'll recognize that $\frac{dS}{dt}$ denotes the change over time of $S(t)$, which refers to the susceptible class. But what's going on with the right-hand side? First, we've got some stuff we call "demography" - birth and death rates denoted as $\Lambda$ and $\mu$ respectively. We don't have anything complex like mating dynamics - we just have a constant birth rate $\Lambda$ - but that's ok, it's the kind of simplification we make when the model isn't being used to study that, and that allows us to get some traction analyzing the model. The death rate, $\mu$, is not time-dependent. This is another simplification. It amounts to saying that the rate of death is constant at all times for the population - an exponential decline term. Again, we're not doing any complex modeling of lifespans here, so it's reasonable for our purposes. We'll talk about the demography a little more when we get to the disease-free equilibrium (DFE).

Since we're using this model to talk about disease dynamics, the most important term here is the $\beta S I$ term. Being negative, the term indicates individuals leaving the susceptible class. So they leave the class, and they're not dying. Where do they go?

Well, if we look ahead to the infected class, $I$, we see this is where they go when they leave. If you've ever looked at chemical kinetics, you might recognize this as a mass action interaction, where the rate of a reaction is directly proportional to the concentrations of the reagents. For the sake of the analogy here, an interaction between a susceptible person and an infected person produces a new infected person, with force of infection $\beta$. So the infected class grows with this mass action term as infected individuals create more infected individuals from among the susceptible population.

What else do we have on this line? Well we have the demography again in the $-\mu I$ term, indicating a natural death rate - natural in that it's the same as the susceptible class, so we don't have any disease-induced death here - and a $-\alpha I$ term. So for those, again - if they're not dying, where are they going?

Look ahead once more at the last line, where we have the change in time for the recovered class, $\frac{dR}{dt}$ encoded. Note here we have a positive $\alpha I$ term to match the negative term in the infected class - so this is where they go! So $\alpha$ is the recovery rate for the infection. The only way people leave the recovered class is through natural death, $\mu R$.

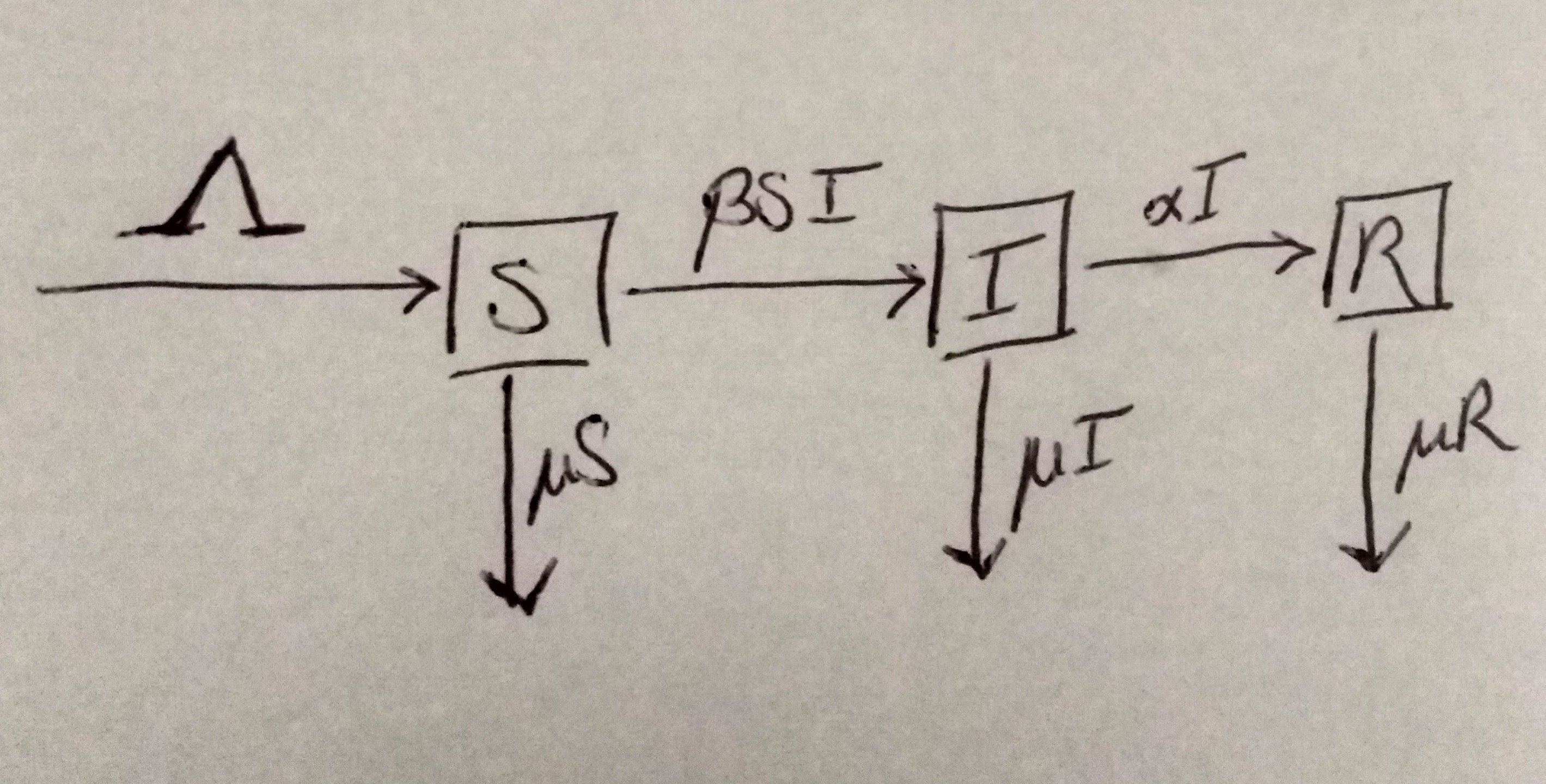

Since that's a lot of text and equations, let's summarize with a flow chart:

Before we get too far along, I want to point out a couple things. I've already drawn attention to the fact that the model does not have disease-induced mortality. Specifically, that all classes have the same death rate, $/mu$. We also have instantaneous infectivity in the infected class $I$. If you've heard of an SEIR model, where E refers to the exposed class, this is a more standard way to bake a delay in infectivity into the model. The alternative is to build it as a delay differential equation (DDE) which are terrible beasts and not for the faint of heart.

"Great, there's a cute little model here, but what can you do with it? I don't want to do a bunch of calculus to find analytical solutions" you say.

And I'd respond, "Wonderful! Because as of right now I only want to find equilibria, and that only requires some algebra."

That's one of the fun things about dynamics - though it's worthwhile to find analytic solutions where we can readily, we recognize in many cases that's not possible. In fact, it's more often than not the case with nonlinear models that you can't get analytic solutions! Instead, we try to find equilibria and the corresponding regimes where solutions converge to those equilibria over time.

So what's an equilibrium of the system? Well, if you think back to calculus, if the derivative of a function is zero, it's constant (unchanging). That's what we're interested in here. In this case, if all of $\frac{dS}{dt}$, $\frac{dI}{dt}$, and $\frac{dR}{dt}$ are 0, it means the size of each class is staying the same. A word of caution: it doesn't mean there's no movement between classes at all - just that, if people are entering the class, the same number are leaving it.

So first, let's look at that disease free equilibrium (DFE). As a simple check, any epidemiological model should have one of these - it needs to describe in at least some detail what the population pattern is in the absence of disease. It doesn't need to be particularly interesting, since, again, our goal isn't capturing mating patterns, but it needs to not be something absurd.

The DFE basically answers the question, "What does this population do if there's no disease at all?" and the way it answers that is by just setting $I$ and $R$ to zero and seeing what happens. At a glance, if $I = 0$, then there's no one to infect anyone in the susceptible class, and also no one moving into the recovered class. That means we can just look at the susceptible class equation: $\frac{dS}{dt} = \Lambda - \mu S$. For the equilibrium, if $\frac{dS}{dt} = 0$, then we know $\Lambda = \mu S$. That tells us that the size of the susceptible class in equilibrium is $S = \frac{\Lambda}{\mu}$. This is the value for which the birth and death rates are the same.

There's a little fine detail about the recovered class - we assumed $I = 0$, but didn't make any assumption about the recovered class $R$. And that's ok! We don't have anyone entering it if $I=0$, and only have people leaving it through natural death, so if it's nonzero, it must be decreasing. So the DFE is $S = \frac{\Lambda}{\mu}$, $I = 0$, and $R = 0$.

Under construction